‘Faces of Incarceration’ hopes to reverse stigma imposed by society

Faces of Incarceration Gallery

August 28, 2017

Pat Dillon knows first-hand there is often much more to the story of how someone becomes caught up in the justice system than what others learn. Oftentimes, children are victims of abuse, neglect, or poverty. Some are introduced to the system after being wrongfully convicted.

She believes the cycle of incarceration seems to “lock them up and throw away the key,” regardless of the circumstances.

Dillon was the collaborator and creator of the exhibit, “Faces of Incarceration: Changing the Narrative,” which was on display in The Overture Center’s Playhouse Gallery until August 27.

For Dillon, the inspiration to begin this project came from a yearly meeting,where Madison police, the district attorney, FBI and other agencies call in Madison’s “top ten” offenders and, after a long discussion on crimes they’ve already committed, have them sign a contract stating that if they get into any more trouble they will be given the maximum sentence for that crime. Used as a deterrent to future criminal acts, this agreement can have someone sent back to the prison system for the smallest of offenses.

During the session, they project a face of a known criminal onto the screen. In this case, it was the father of Dillon’s grandson – a mug shot of him when he was 17 years old. At the time, he was 28 and enrolled at UW-Platteville in the distance learning program.

Everyone in that room perceived him as neither a good student, nor a good father, or any of the things Dillon knew him to be. He was just labeled one of Madison’s top drug dealers. Despite living with an addicted mom, and being homeless while going to school he still managed to get straight as while attending high school.

“Faces of Incarceration” aims to reverse the stigma imposed on people who are caught up in the criminal justice system. It shows that many emerge to live lives of dignity and extreme purpose according to Dillon.

The exhibit is also meant to shine a light on systems of inequality in the prison system. “Wisconsin has the highest rate of incarceration of people of color than any state in the country,” said Dillon.

Dane county alone incarcerates people of color at a higher rate than the rest of the counties in Wisconsin, according to a report released by the Wisconsin Council on Children and Families, a Madison-based liberal advocacy group. The report said that in 2012, African-American adults were arrested in Dane County more than eight times that of whites.

“When they or any person returns to their community after the trauma of incarceration, they are more often stigmatized than embraced, vulnerable to revocation for non-criminal acts, and locked out of opportunity such as adequate housing and life sustaining work,” Dillon said.

As far as the bigger picture for the exhibit, Dillon hopes to create “empathy among populations who don’t spend time thinking about these systems and institutions.”

One of Madison College’s own students sat for portraits for the exhibit. Adrian Molitor had been introduced to the project through the local art community, having previously sat for portraits with a couple of artists.

Molitor had already been incarcerated before, and had watched the injustice of the system against his own friends. People he had known much of his life were getting five to ten years while he was getting away with probation.

On his ability to escape the cycle of incarceration, “I think that has to do with the fact that I’m a white male, and I was given other opportunities that a lot of my friends growing up didn’t have,” Molitor said.

“I think to the common person it should be disgusting and alarming to see the system eat itself from the inside out, it kind of perpetuates this huge money drain on our society, not to mention the loss of members of the family that it represents.” Molitor himself has his own family. Being a good father to his twin sons has helped motivate him to get back on track.

Here at Madison College he also serves as a mentor and tutor with the TRIO program. He hopes to become a social worker, and work within the public-school system or the prison complex. “I felt pretty good to hold my space as a white male in America that’s been convicted of felonies and has facial tattoos and is basically unemployable by some standards, as a person that made it out of all of that stuff. It’s empowering.”

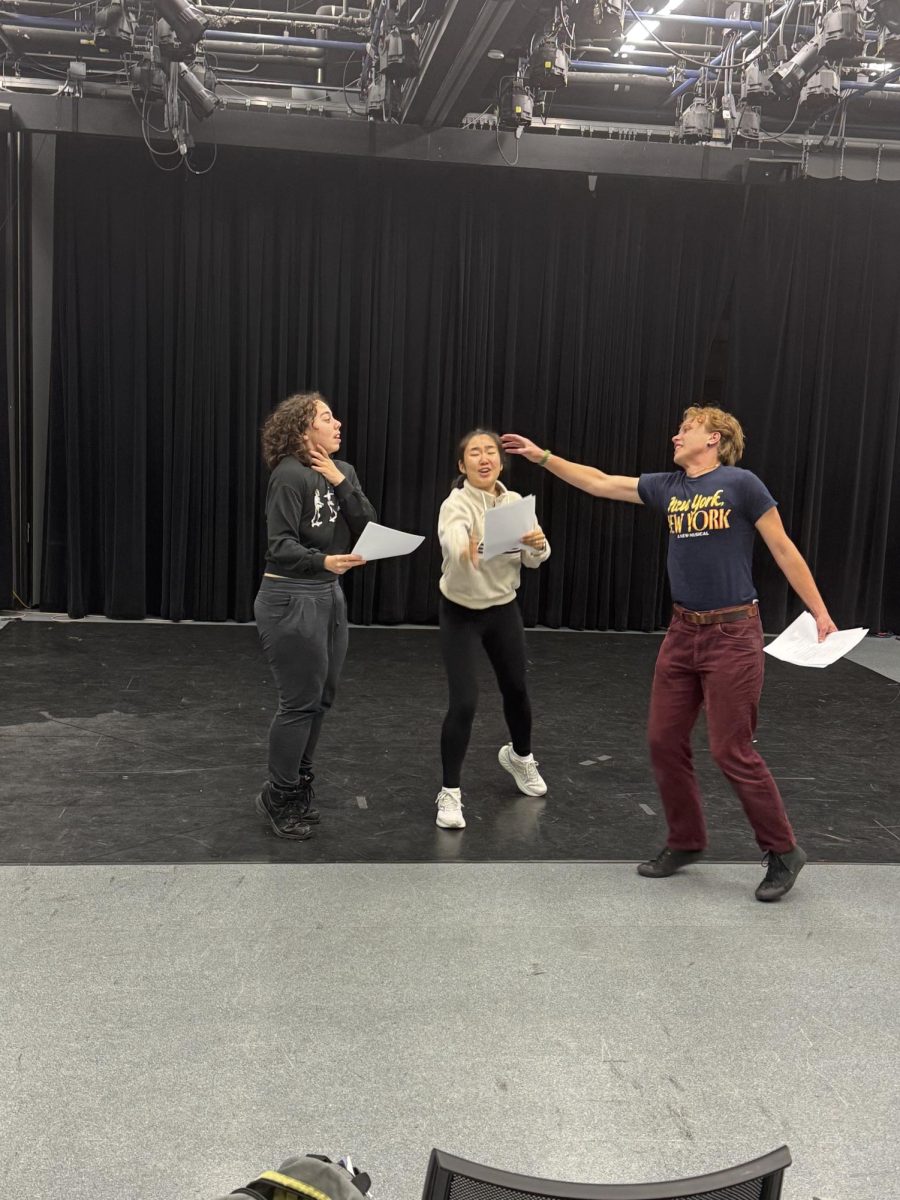

The portraits, while done in varying styles by varying artists, seem to evoke a part of each subject’s personality. Even though three portraits of the same person look very different, they gave off a sense of unity.

When asked to pick a favorite portrait, Molitor couldn’t pick just one, but said of the experience “The power that I felt when I was surrounded by all of them… Just that feeling which was visceral, it wasn’t any specific one, it’s interesting to think of how much power was in that room.”