An entire generation, tens of thousands of children, vanished after a decade of war in Nepal. Some were taken by Maoist rebels and forced to take up arms against the king before they had even reached puberty. Others fell into the hands of traffickers who, for a fee, promised impoverished families a better life for their children.

Instead, children as young as three were abandoned, sold, starved or used to draw the attention of sympathetic tourists. If they were lucky the children found their way to an orphanage such as Little Princes.

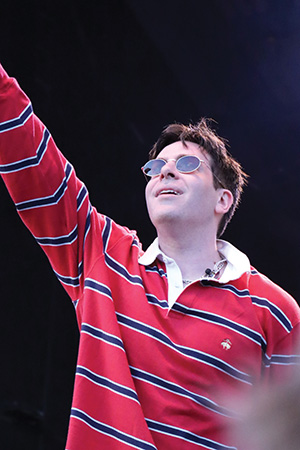

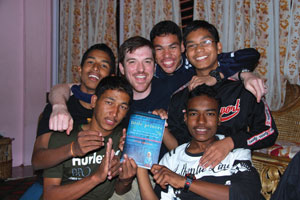

Conor Grennan spent the first three months of a trip around the world volunteering at Little Princes, which is located just outside of Katmandu. His experience would later lead to a published book and the establishment of Next Generation Nepal, a New York based non-profit.

When Grennan arrived in Nepal at the end of 2004, he quickly realized that he had underestimated the intensity of both the war and a house full of children. The only context he had was commercials asking people to sponsor children. What he expected was a sad and desolate place with quiet, sad children, but what he got was entirely different.

“All the kids were just nutso,” Grennan said. “It was extraordinary. They just sort of jumped all over me. All they wanted to do was to have this kind of new play toy and have a great time, and also I think be hugged.”

During his stay at Little Princes, Grennan came to know the children as family. Before leaving he made up his mind that he would be returning, and about a year later he did. During his second stay he learned that the children he had come to love at the orphanage were not orphans at all.

The realization came when a woman knocked on the gate looking for her children. Instead of running to their mother after being separated from her for so long, the children appeared terrified.

In his book, “Little Princes,” Grennan described the heartbreaking scene and explained that the children had been instructed by a child trafficker named Golkka to tell everyone that their parents were dead. If they didn’t they would likely be beaten. Being an orphan was more effective in getting donations from tourists and silencing local authorities questioning why one man had so many children.

Sadly, the mother who had been duped into turning her children over to a trafficker had also been pressured by the same man to take in seven children who weren’t hers. With very little money, the woman could not afford to take care of the children so they were nearly starving.

“All of the sudden we realized we were going to have to find a solution for these seven kids who had been trafficked just like our kids had been trafficked,” Grennan said. They thought they had found a safe home for the children, but an intensifying civil war and nervous child traffickers prevented the children from reaching their new home.

Grennan had to leave Nepal, but as soon as he heard that the children had been stolen away by Golkka yet again, he began making plans to return a third time. The desire to save those seven children led to the establishment of Next Generation Nepal.

Instead of just being another orphanage in Nepal, however, Grennan took the non-profit a step further by making it their mission to reunite children with their families. The only real way to do this was to venture into the Himalayas.

For weeks Grennan trekked through remote regions of Nepal with a stack of photos to show parents who hadn’t seen their children in years. The first family, like many others, cried at the sight of their lost child. Still, it was clear that they were in no position to retrieve their child. War and drought made them destitute and another child meant another mouth to feed.

Even though the war drew to a close with a cease-fire in 2006, children continued to be trafficked.

“Parents are still desperate to give their kids a future,” Grennan said. “The huge majority, 90 percent, will never see their kids again.”

Grennan estimated that Golkka alone has trafficked upwards of 1,200 children, and has been responsible for the trafficking of somewhere around 15,000. Next Generation Nepal has located about 400 families, and out of those less than 50 have actually been reunited with their kids.

“We would like to say that (Golkka) has been brought to justice, but the fact is he is now the head of a local political party,” Grennan said. “That is corruption in Nepal. That’s what we are sort of up against.”

Golkka isn’t the only problem that the non-profit faces. Once the children come of age, they aren’t likely to obtain jobs because of high unemployment rates.

“What we are seeing is that kids never really age out of orphanages in Nepal because there is nothing to age out into. Even in Katmandu education is very rudimentary, far from guaranteeing a job,” Grennan said. “There is simply no future for these kids unless they reconnect with their families.”

With the proceeds from Grennan’s book, Next Generation Nepal was able to open a children’s home in Humla, which is where the majority of the children were from.

“It was a dream that we had for so many years, to get those kids home, and a dream of theirs too,” Grennan said.