What do Suzanne Collins’ “The Hunger Games” series, Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” have in common?

If you guessed that each one had been the subject of at least one movie adaptation, you would be right. If you guessed that each book, at time of publication, merited a review in the New York Times Book Review, that too would be right. If you guessed that all three titles could be found on the shelves of at least one of the Madison College Libraries, again you would be right. If you guessed that each one had garnered a literary award for its author (a Pulitzer Prize for Harper Lee, the American Academy of Arts and Letters Award of Merit for Aldous Huxley, and a Golden Duck Award in Young Adult Fiction for Suzanne Collins), you would again be right.

What you might not have guessed is that these three titles also shared the dubious honor of a spot on the American Library Association (ALA) Office of Intellectual Freedom’s (OIF) List of the Top Ten Most Frequently Challenged Books of 2011.

What does it mean when we say that a book is challenged? ALA defines a “challenge” as a formal, written complaint, filed with a library, requesting a book’s removal from the library’s shelves on the basis of its content. According to the OIF, which keeps annual statistics on such complaints, there were 326 reported attempts to have materials removed from library shelves in 2011. And the OIF estimates that several times that many go unreported. While the majority of such challenges occur in school and public libraries, they occur in libraries of all types, including academic libraries such as ours.

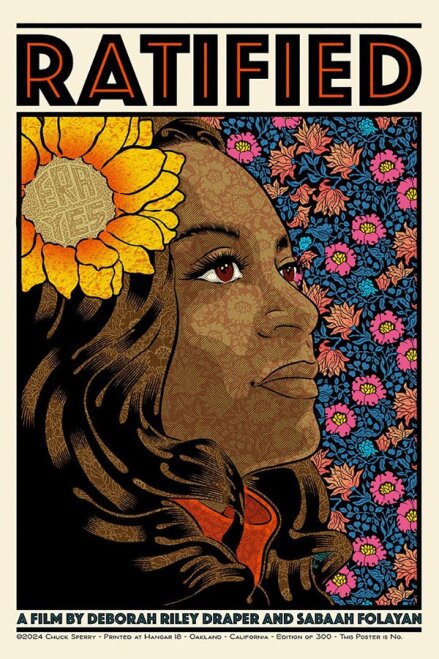

Sept. 30th to Oct. 6th is Banned Books Week. Observed for the past 30 years during the last week in September in libraries, schools and book stores nationwide, the week serves as a reminder that, even in this “enlightened” 21st century, book challenges continue to occur. Each year when Banned Books Week rolls around, I ask myself, do we really need to write yet another column on this issue? After all, give or take a few upsets, the titles on the Top Ten list change remarkably little from one year to the next. But the fact that attempts are made, year after year, to restrict my ability and yours, to read what we choose because someone happens to disagree with a book’s contents underscores the importance of remaining vigilant. The fact that, year after year, students express surprise and incredulity that such attempts occur underscores the continued need to draw attention to it.

The ability to read, speak, think and express ourselves freely is a fundamental right, protected by the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. It is precisely because issues of censorship go to the heart of our constitutionally guaranteed democratic freedoms that these questions are of such importance to the library community and to all citizens.

The Freedom to Read statement, adopted by the America Library Association in June, 1953 ends with the following words:

“We do not state these propositions in the comfortable belief that what people read is unimportant. We believe rather that what people read is deeply important; that ideas can be dangerous; but that the suppression of ideas is fatal to a democratic society. Freedom itself is a dangerous way of life, but it is ours.”

Let us guard against taking this freedom, or the responsibility that comes with it, for granted.

For more information about Banned Books Week, annual Top Ten Lists of frequently challenged books, a 30-year banned books timeline, and more, check out ALA’s Banned Books Week page.