On March 9 of this year we will all once again move our clocks ahead one hour in compliance with daylight saving time (DST). Did you ever wonder why we “spring forward” each year? Is it really all about saving energy or giving farmers more hours in the field? And who or what is really behind this national routine?

Upon investigation, the story of daylight saving time is more convoluted, quirky, and fascinating than anything Hollywood writers could conceive. The central idea of daylight saving time is to make better use of daylight by transfering an hour of morning daylight to the evening hours. First employed during World War I by Germany and its allies, then Great Britain three weeks later, daylight saving time is in use today in approximately 70 countries around the world. Japan, India and China are the only major industrialized countries that do not observe any variation of DST. Equatorial and tropical countries (lower latitudes) generally do not observe daylight saving time since the daylight hours are similar during every season and there is no advantage to moving clocks forward during the summer.

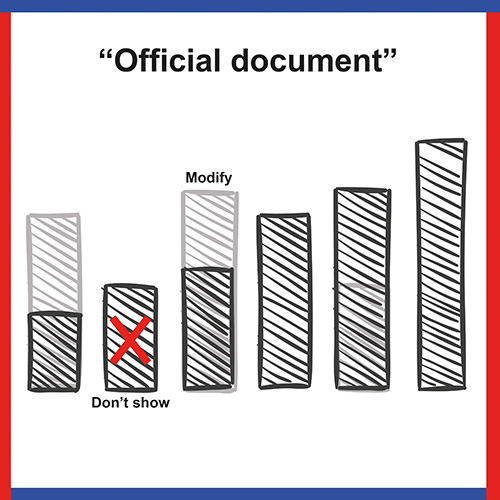

The U.S. Department of Transportation opinion surveys from the ‘70s found that daylight saving time was generally popular with the public, except for the months of November through February. Various studies over the years have attempted to qualify the effects of daylight saving time. Some studies have shown energy savings; others have shown an increase in energy use. Some studies have shown a decrease in traffic fatalities due to DST, others an increase.

The U.S. Standard Time Act of 1918 established seven months of national daylight saving time each year, and legally sanctioned the railroads’ four time zones — Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific — and added a fifth zone, Alaska Time, for all of Alaska. This act was designed to appease the railroad industry, which had opposed daylight saving time and was concerned with the potential dangers to the railway system in turning the nation’s clocks forward.

D.C. Stewart of the American Railway Association was asked by U.S. Sen. Frank Kellogg (R-Minnesota) at what point in the day the fewest number of trains were running. Stewart replied, “Two-o-clock in the morning”, thus setting 2 a.m. as the designated transition time in the bill and in all U.S. DST laws since.

Our current DST schedule was part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which extended daylight saving time from the second Sunday of March to the first Sunday in November.

If you’d like to know more, two books were published in 2005 on the history of DST – “Seize the Daylight: The Curious and Contentious Story of Daylight Saving Time” by David Prerau and “Spring Forward: The Annual Madness of Daylight Saving Time” by Michael Downing.

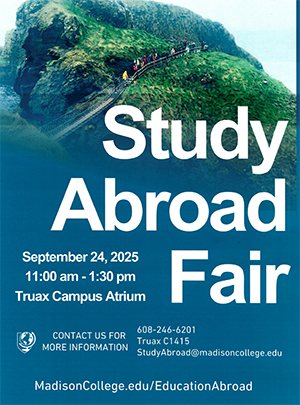

Students finding themselves missing that lost hour and needing more time in the library are in luck. Beginning March 23, 2014, the Truax library will be open on Sundays from noon to 6 p.m. for the remainder of the spring semester.