Woodward and Bernstein offer lessons of past

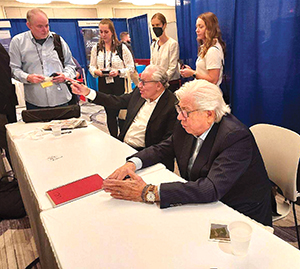

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, right, meet, with students at the MediaFest22 convention.

November 9, 2022

You always know pop stars are about to speak when people are clamoring for seats in overflow rooms. A half-hour before the scheduled keynote address, it was hard to ignore the growing excitement of the gathering crowd.

Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were about to address the more than 800 attendees at MediaFest22.

Members of the Clarion staff attended MediaFest22, the five-day convention, a journalism conference jointly presented by the Society of Professional Journalists, the Associated Collegiate Press and the College Media Association.

The Clarion editors participated in the five-day conference from Oct. 26 to 30, attending sessions on various topics, including the principles of photojournalism, the importance of local news and ever-changing social media.

On the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in, legendary reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were the keynote speakers at the conference.

In 1973, Woodward and Bernstein were awarded the Pulitzer Prize for their Watergate coverage at The Washington Post, leading to the scores of government investigations, and eventually, the resignation of President Richard Nixon.

The duo went on to write two classic best-sellers: “All the President’s Men” (also a movie starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman) and “The Final Days,” describing the last days of the Nixon presidency.

Fifty years after the iconic events, the two reporters answered questions about investigating the story and how they broke it.

Woodward explained he had only worked for the Post for about nine months but was so enamored with reporting he often stopped in the office on his days off.

“Now, June 17, 1972, was one of the most beautiful days in Washington, ever … when the paper got word of a break-in at National Democratic Headquarters,” he said. From what Woodward understands, the editors asked themselves who would be dumb enough to come in on a gorgeous day and work?

The city desk promptly called Woodward.

They told him to head to the courthouse where the Watergate burglars were about to be arraigned.

At the courthouse, Woodward noticed the burglars were all dressed in business suits, not everyday clothing for a criminal. The attire alone got his full attention.

However, the biggest red flag occurred when the judge asked one of the burglars where he worked. When the burglar told the judge he worked at the CIA, Woodward knew he had entered uncharted journalistic territory.

Bernstein continued the dialogue, saying he was working in the newsroom doing a story about a candidate running for governor of Virginia when he suddenly heard a commotion by the news desk. Bernstein walked over to see what was going on.

Somebody told him there was an overnight break-in at the Democratic National Headquarters.

“It seemed like a better story than I was working on, so I said, ‘I’ll make a few calls,’” he said.

Bernstein later called an ex-girlfriend to get the list of employees on Nixon’s re-election committee, beginning at the lowest rung by interviewing the committee’s bookkeeper.

Along with sharing compelling and humorous anecdotes about the most significant political story of all time, the two offered advice on investigative reporting.

Woodward offered the audience advice on interviewing sources, including the power of showing up, something the two of them don’t believe happens enough today.

The two said one of the first things they did when starting the story was to start making calls and knocking on doors immediately.

The ability to show up is a skill they’ve continued to do throughout their career. They mentioned it is too easy to email or text a source when interviewing in person offers more insight and information.

The two say they believe there are too many cases today of journalists just mailing it in.

“We need to show up … We are not showing up enough,” Woodward said.

They enlightened the audience on the importance of gathering information from low-level sources.

Woodward said he learned from Bernstein the type of people made for the best sources.

“Find people at the lower level,” Woodward said. “That’s what Carl taught me. We can’t go to the White House and ask people about this, so we have to knock on doors, and that’s the Bernstein method.”

In the early days of Watergate reporting, the best sources were the desk workers and low-level employees, those who knew what was going on because they often were the ones who had to file forms and document events.

The pair was asked to assess former presidents Richard Nixon and Donald Trump.

Bernstein and Woodward compared the two former presidents by how they treated the media by quoting Nixon while he was in office.

“Never forget, the press is the enemy. The establishment is the enemy. The professors are the enemy. Write that on a blackboard 100 times and never forget it,’” Woodward said, quoting Nixon from December 1972.

“It was unimaginable to us that anything could surpass what Nixon had done in terms of criminality, in terms of undermining democratic notions … and then along came Donald Trump,” Bernstein said.