Syria, once inhabited by over 26 million citizens across various regions, boasted different cultures, backgrounds and religions. Known for its thousands of years cultural heritage and deep significance in the Middle East, the country has recently received international recognition due to a significant humanitarian crisis over the past decade. So, how did an initial call for freedom evolve into a desperate struggle for survival?

Despite the Arab Spring, a series of uprisings and protests, bringing global attention to the issue, the plight of the Syrian people began before 2011. In 1970, following his coup d’etat Hafez Al-Assad, was elected president, ironically the only running candidate.

Many thought Assad would bring the country stability, but his rule saw high inflation rates and increased poverty rates, resulting in dire living conditions and a compromised workforce.

Syrians faced the challenge of navigating their lives with limited resources. Following his three-decade rule Hafez died, and the parliament changed the constitution in 30 minutes session, to allow his son -under 40 years old- to run for office. Bashar assumed power in July 2000. It was a time marked by heightened political activism and calls for democracy, all of which were crushed with iron fist.

The Syrian Revolution, which began in March 2011 amid the Arab Spring, saw its people initially participating in a series of protests that tragically escalated into substantial bloodshed. This revolt aimed at challenging the authoritarian rule of the Syrian government and President Bashar Al-Assad.

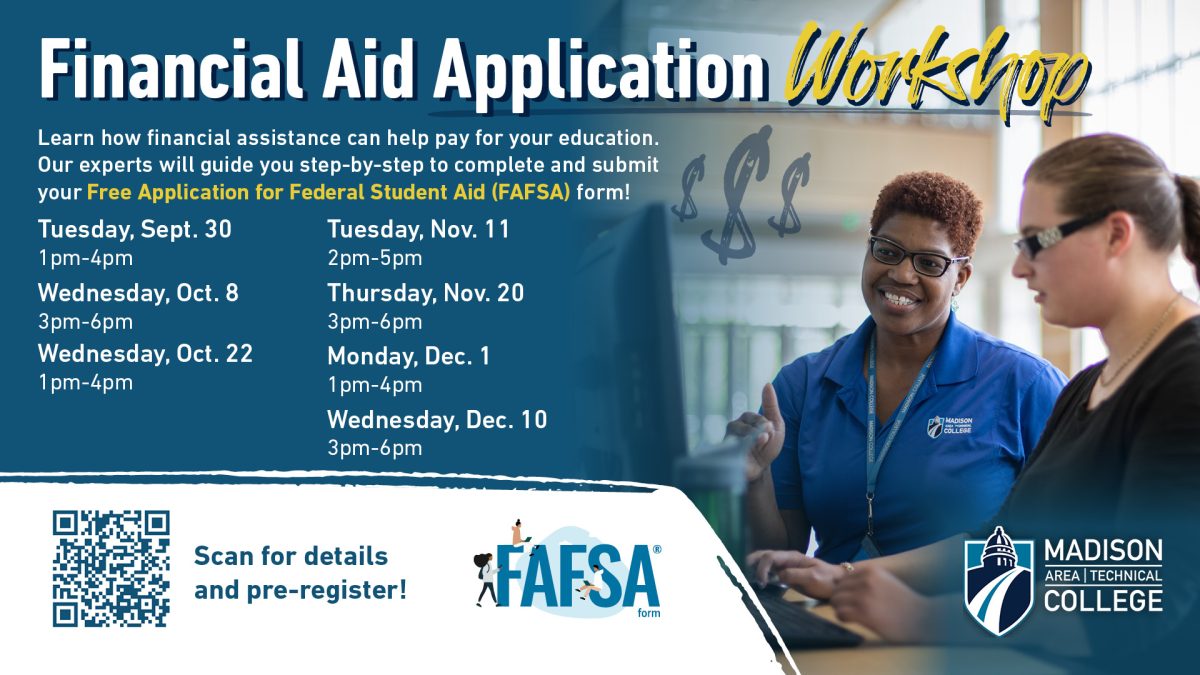

I recently attended a lecture held by two Syrian speakers at Madison College, Iman Alrashid and her husband Chadi Kadour (Syrian women keep their family name after marriage).

Luckily a twelve years old immigration application came to life just in time, allowing them to escape with their three young children in February 2012, seeking refuge from the dangerous conditions. Their journey for a brighter future brought them to America, giving them the chance to voice the injustices they endured in their homeland.

As the revolution unfolded, Chadi and Iman hoped that it would be a brief disruption, allowing them to return to the normalcy of their daily lives. Chadi, once an assistant manager in a successful IT company, and Iman, a dedicated teacher, had a prior life of stability and beauty, a stark contrast to the escalating poverty.

Describing their experiences in Damascus during the revolution’s onset, they shared heart-wrenching stories where they faced soldiers, armed and loyal to Assad, at checkpoints. These soldiers had the authority to detain and execute anyone for no reason. Their family encountered these checkpoints daily.

Iman described these checkpoints as being so dangerous that they were “a fight for survival every day,” which led her to eventually stop working and send her kids to school. However, this meant that Chadi and many other Syrian men were forced to continue working, often putting in extra hours to secure money and food for their families.

In the eighth month of the revolution, Chadi, Iman and their children were returning to their home on the outskirts of Damascus after visiting his parents. While driving, they encountered a checkpoint barricading the road. Typically, the stationed soldiers would create any excuse to deny civilians their destinations.

Iman recalled that day to the audience, offering a glimpse into their harrowing experience. “It was a dark night devoid of any distant light to be seen. All of a sudden, we found two soldiers beating up a man in front of his van. They kept kicking him until he either lost consciousness or passed away… I could not tell,” she said.

Iman said her children were sleeping in the back, and Chadi had to give them a lot of money in order to let them pass. “As we drove away from the checkpoint, I turned around and noticed my 10-year old daughter, with her eyes wide open, full of fear, asking me questions that I simply could not answer,” Iman said.

Within the strict Assad regime after 2011, going against the government in any way was illegal, it could lead to death or imprisonment, meaning the regime suppressed freedom of speech and thought, and weaponized both religion and fear.

Propaganda campaigns linked Syrian activists to extremist groups like Al Qaeda, creating a negative image of those calling for freedom calling them terrorists. Religion was a tactic manipulated to fuel hatred, causing fractures among the Syrians. Some supported Bashar, while others did so fearfully. The regime’s exploitation of fear enabled Assadist soldiers to prey on vulnerable individuals and their resources.

Checkpoints were a perfect way to prey on people. Iman described it as a manipulative game. On their way back home after their encounter at the first checkpoint, they came across a second one.

Chadi rolled down his window and greeted the soldier, who then yelled for Chadi’s ID. Upon its retrieval, the soldier forcibly took Chadi’s wallet and noted his place of origin. Reacting to the information, the soldier hurled insults upon seeing the identification that indicated Idlib, a city known as a refuge for individuals opposed to Assad.

Idlib, labeled as the rebel area, was strongly disliked by many Assad supporters. Iman explains that afterward both soldiers held a flashlight close to their car. They also carried their rifles. By this point, her daughter and son were awake. Despite the soldier sensing Iman’s fear, he approached with the gun and flashlight, pointing the light on her one year old son, attempting to rouse him as a form of threat.

Another soldier pulled Chadi out of the car and walked away, and another sat in the drivers’ seat, next to Iman. Iman describes how the soldier fiddled with the flashlight, well aware he was frightening the family.

However, Iman’s fear was soon replaced with anger. Minutes later Iman saw her husband return to the car. Their children asked him if they were going to die that night.

Chadi described his encounter, saying the soldier repeatedly questioned him, but instead of being fearful, he boasted with pride about his father’s experience in the first battalion.

“Back in the ‘80s my father, a general, was one of the leaders of the first battalion. This land is one that I’ve walked on over a thousand times, long before you were even born, so this is my land,” Chadi said to the soldiers.

He believes his swagger struck fear in them instead, as playing with fear was a known tactic for the people, and somehow, he let Chadi go.

“My arrogance helped me greatly that night,” Chadi said.

Today, more than 200,000 Syrians are still missing, with over 12 million displaced across the globe, and over half a million documented deaths. The revolution may be long-forgotten but it continues to this day. The ongoing terror that Syrians endure remains a stark and ever-growing reality.

Editor’s note: The Madison College journalism student who wrote this article asked that her full name be withheld out of concern for family members still in Syria.