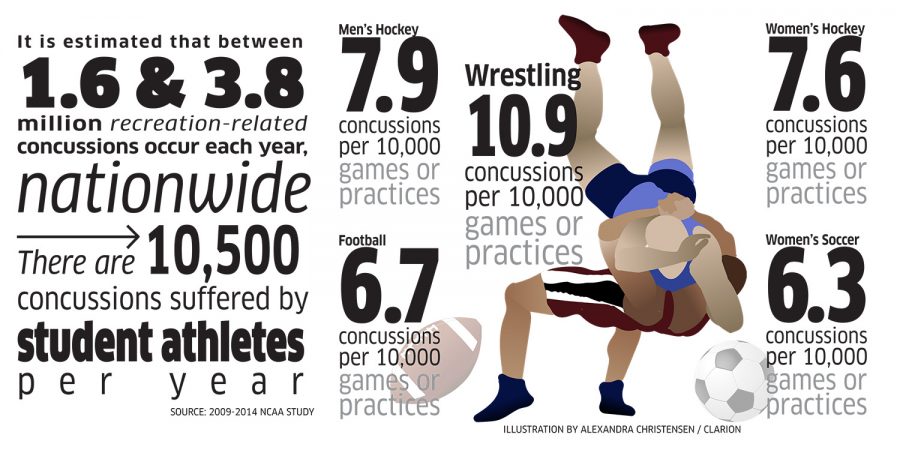

Statistics gathered by the NCAA from the fall of 2009 through the spring of 2014 show the frequency of concussion in some sports.

Dealing with concussions

College’s multi-step protocol protects athletes from long-term problems

February 13, 2018

Diving for a ball and hitting her head, Peyton Trapino got up thinking nothing of it. As a basketball player for Madison College, she’s used to throwing herself into the fray.

Though bleeding from her head, she wasn’t too concerned, just ready for the next play.

Finishing the game and going home, Trapino started to feel sick – was a little nauseous, felt dizzy and had a headache.

“It was a lot of testing after that, like balancing. A lot of tests, and you have to past them and get cleared,” said Trapino.

She found out she had a concussion.

“I was kind of surprised,” she said.

Concussions in sports are often associated with the big contact sports: football, hockey and wrestling. It’s not something that people associate with women’s basketball.

But, as Trapino learned, a concussion can occur in almost any sport.

Madison College has a specific protocol players must go through if they sustain a concussion. The protocol was established by the UW Health Sports Clinic and Mike Van Veghel, who is employed by the clinic and is the athletic trainer for the college.

A concussion isn’t always the result of a direct blow to the head. Van Veghel describes it as the rapid acceleration and deceleration of the brain inside the skull. The brain will be thrust into motion and, having nowhere to go, it hits the side of the skull and can ricochet back and forth until it stops moving.

Once it was confirmed Trapino had a concussion, the college’s protocol kicked in. She was removed from all team activities and had to wait for her symptoms to subside.

Most concussions that occur are what Van Veghel calls “mild.” The symptoms usually go away after a day or two and the player can be reevaluated.

Players fill out a sheet that has a list of symptoms and a rating of how severe they are. Trapino’s worst symptom was a headache that wouldn’t go away. It stuck around for a week, and even kept her home from school. She sat at home waiting for her symptoms to subside.

Letting a player return to any kind of physical activity, especially any that may involve contact, too early is extremely dangerous. Van Veghel calls it a “window of vulnerability,” where, if another concussion occurs it will do even more damage and could become a problem that affects brain function.

A player at Madison College can’t start the progression of coming back until they are symptom free for at least 24 hours. Van Veghel cautions that “a player feels better before their brain returns to normal function.”

Once Trapino’s headache finally subsided, she could start the exercise progression of the protocol.

It started with stationary biking to see, if raising the heart rate brings back any symptoms. If no symptoms occurred then the athlete can move on to biking in intervals – biking for 45 seconds, then stopping, and then biking again. Van Veghel said this is a more realistic representation of what the athlete will go through during live action.

If no symptoms occur, the athlete is allowed to move on to jogging, to see if the actual jogging motion will cause symptoms.

The protocol is a step-by-step progression to see if any type of movement or raised heart rate will cause symptoms.

If Trapino were to get a headache while jogging she would have had to go back to biking at intervals. A player that gets symptoms again goes back to the last completed stage of the protocol.

The next stage of protocol is for the player to start limited activity in practice.

For Trapino, that meant some team drills, but still no contact. Van Veghel calls it staying away from “uncontrolled situations” where a player could possibly get another concussion.

After that Trapino could participate in a full practice but not a scrimmage, which is an uncontrolled situation. Scrimmage would be the last stage, no more restrictions.

Once she reached that stage, Trapino could play with reckless abandon once again. And for her that’s exactly how she still plays.

“I still dive every single game,” Trapino said about playing after her concussion.

The concussion protocol can be a slow process but it’s all about making sure the symptoms don’t reappear at any stage.

“Big, long annoying process, but it’s for your health so I guess it’s important,” Trapino said of the protocol.

But what can make the process easier is having an athletic trainer that you can communicate with to help you through the process.

“(It was) super rewarding when I got back eventually,” Trapino said. “I was with him (Van Veghel) everyday annoying him, but he did an amazing job.”