His first chance to cast a ballot in the United States has been a long time coming for Jovhany Michaud.

On a Wednesday morning during a WolfPack Welcome event last summer, Michaud found himself waiting among a group of students stationed at a video camera and filling out forms. A variety of first-time voters were asked to share their feelings about the upcoming election.

Although most agreed to be interviewed, many students were reluctant to talk. When they opened up about first-time voting, most shared the same feeling – fear – in the form of nervousness, apathy and anxiety.

But the vibe quickly changed when it was Michaud’s turn to speak. He was enthusiastic and ready to talk. His excitement was palpable, and he chatted about visiting the polls and casting his ballot.

After arriving in the United States from Haiti in 2017, he received his citizenship late last year and he’ll be voting in his first presidential election in November.

“I’m excited because this is my first time,” said Michaud, laughing and shaking his head. “In my country, we don’t trust our officials,” he said.

A paralegal student at Madison College, Michaud shared many concerns that will move him to the ballot box, including immigration, jobs, education and free community college. But as he spoke, he grinned and joked, a stark contrast to his peers.

“I have a voice, and I have to cast it. That’s how I see the first time voting,” the 29-year-old Haitian American said.

He appreciates the importance of service to others, like working in the food pantry or attending a meeting with the Black Student Union, La Raza Unida or United Common Ground.

He’s determined to serve people, whether they’re Haitian or American. To understand Michaud’s commitment to the present, you first need to understand his past.

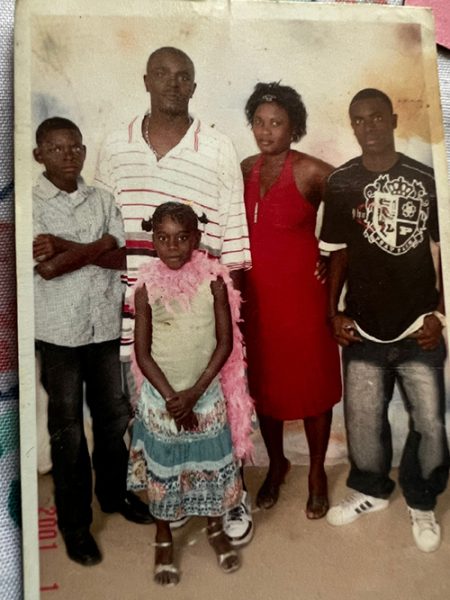

Jovhany Fidel Michaud was born in 1995 in Delmas, Haiti, and he grew up in nearby Tabarre. Both cities are in the metropolitan area of Port-au-Prince, the epicenter of the devastating 2010 Haiti earthquake.

Despite daily waves of violence, Michaud, the second of three siblings, enjoyed his childhood. There were peaceful moments he cherished. He remembers watching soccer games and gathering friends to witness any match, whether televised or live.

He wasn’t always on the sidelines. Michaud often played the sport, seeing it as a way to escape.

Soccer is a sport where only a ball and a field are needed. Haiti has plenty of abandoned spaces, so he often joined the other kids in an impromptu game.

Since he was unaware of any life outside of Haiti, it also served as a way to cope. “Because you didn’t know any better, it’s like you’re satisfied with what you get,” Michaud said.

You may not recognize his name, but you’ve probably seen Michaud around campus — tabling a WolfPack event, greeting new students, storing supplies in the food pantry, presiding over a student senate meeting or attending one of his many club meetings.

You’ve also seen his character in every American immigrant you encounter — hardworking and ambitious, optimistic and curious, leaving their country behind in search of a better life.

In Haiti, violence is embedded in daily life, from the time the country rebelled against French colonists in the late 1700s to recent decades of political instability.

Looking back, Michaud realizes there were always dangerous places in his country, but people were warned of them, and they heeded the warning. He said these days are different.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s in the morning. If it’s in the evening. There is still a chance that you may be kidnapped or killed,” he said.

Among the many protests he’s seen, Michaud vividly remembers the weeks-long conflict of the 2004 Haitian coup d’état, resulting in the removal of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide from office. Only 9 years old at the time, he witnessed the unrest unfold with burning cars, billowing smoke, gun battles and boys toting sawed-off shotguns.

In 2017, his grandmother urged him, his father and his sister to leave the country, which was the first step in coming to America. (His brother and his mother, under President Biden’s Family Unity Immigration Initiative, joined them last year)

Michaud’s journey took him to Florida, but a housing issue moved him to Wisconsin Dells, and he admits he had to Google “Wisconsin.”

The Dells gave him employment and independence, but he knew he needed more human connection, so he moved to Madison.

After COVID-19, he recognized he needed more advanced schooling but didn’t know how any college could accept him. It wasn’t a lack of education holding him back since he already had a diploma, but it was the fact that the document originated from Haiti.

“To go back to my roots. Any paper from Haiti won’t have any sway in the United States. It’s just going to make it hard for you,” Michaud said. Realizing he could not persuade anybody of his high school diploma, he decided to pursue his High School Equivalent Diploma.

That all changed when he met a Madison College advisor who suggested the Dual Enrollment Program, which allows for a high school and college degree.

Given his extroverted personality, it’s no surprise that Michaud would want to meet people. He attended one of the many WolfPack events and had the chance to visit the Student Senate, where he found his life making a hard left return, opening many avenues.

He had no idea what a Student Senate was, let alone that the membership had a voice. He was astonished the students had a say.

“Really? I always want to help people. That’s why I do so many things. I always want to help. Seeing students have a voice here – in my country, students don’t grow up like that,” he said.

Michaud said that in Haiti, students are voiceless. They are more responsible for parties, buying T-shirts and socializing. He recalls an incident at his high school where the director sent the entire student body home, whether or not they were involved.

“There was no power. After being in the Senate, I see we own some power,” he said.

Michaud later decided to run for Student Senate president to help people, winning the race and heading the organization from 2023 to 2024.

Now that he is settled in America, his advice for other immigrants is simple. “Try to connect with people. Don’t treat it as you’re just passing (through the country) because you’re lying to yourself,” said Michaud, suggesting they avoid getting caught up in two worlds and only focus on the United States.

“Because most people come here have this mentality like ‘I’m just coming here to save and to go back.’ But in reality, you never will go back,'” he said.

He sees other immigrants convinced that they could save money and return to their country, but he said they have already accustomed themselves to a certain lifestyle, making it impossible to return.

Michaud encourages other immigrants to take advantage of being here, use their voice, create opportunities and focus on goals.

“Treat this country as the only one you got,” he said.