Globally, epilepsy affects over 50 million people, with a significant number residing in Africa. It is the most common neurological disorder in Africa, affecting approximately 25 million people, making it the most widespread neurological disorder on the continent.

One African country, the Sub-Saharan Burkina Faso, in particular, endures even more challenges because of the disorder. A study of three rural villages revealed a high epilepsy prevalence of 44.27 per 1,000 people, with an association found between epilepsy.

Burkina Faso has a population of 23.03 million. Now, compare that number to another number…nine.

Nine. Nine neurologists. How do you treat this neurological disorder in a county where 4.43 percent of its population has epilepsy?

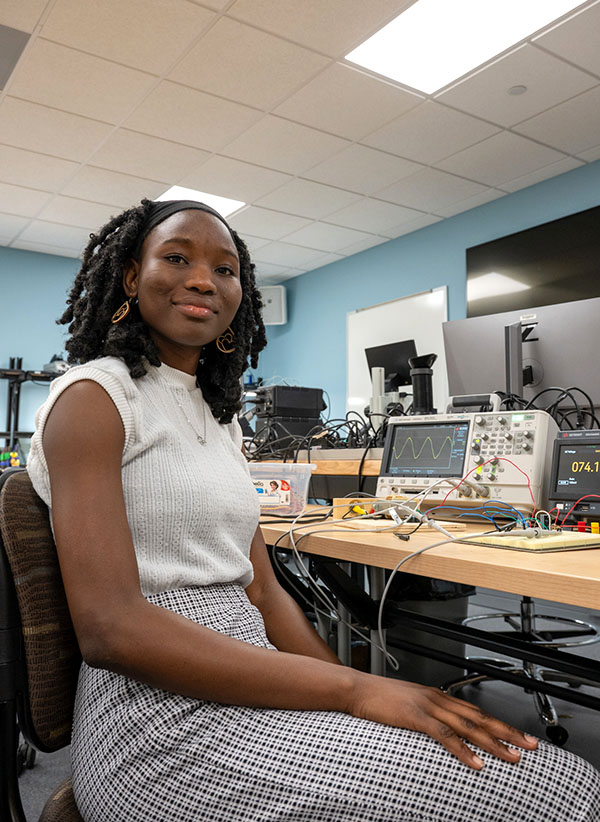

Burkina Faso is the birthplace and home of Madison College Honors Program student Teegawende “Josephine” Segrado. While she speaks lovingly of her home country, like most villagers, she comes from an impoverished family.

“In Burkina now, it’s a developing country in the sense of the word because right now it’s trying to strive for electricity access and education. We are working to get a decent lifestyle for everybody right now,” said Segrado. “It’s a place where people know what they want, but it’s hard to get it.”

Segrado has always dreamed of the opportunity to further her higher education goals and study electrical engineering. After a rigorous testing and preselection process, learning English, computer training, public speaking, and a year of waiting, she received her visa in the summer of 2023, came to Madison and enrolled at the college.

She participates in an endless list of extracurricular activities. She is a member of Phi Theta Kappa, a Peer Health Educator and the Alternative Winter and Spring Break coordinator at the Volunteer Center. But behind the hectic schedule of robust activities, friends, and homework, there is an urgent need. Her dream has now taken on another purpose.

Segrado has five siblings. She has one older brother and two older sisters, all married and with children. Her father passed away in January and her mother now lives with her young brother Wendtoin (Josephat), 20.

Josephat is studying for his baccalaureate. He has always been the entertainer in the family, smiling and happy-go-lucky, talkative and always telling jokes.

Some time while Segrado was waiting for her visa, the laughter in her household began to fade. Something was off with her brother. Josephat started having seizures in an epileptic episode.

There is no pathway to treating epilepsy in her country. There is little access to hospitals. Even when you are admitted to one hospital, you still have to wait to see a specialist for your condition.

More often than not, most epileptic patients are not even treated with a prescription. In so many words, they are told to accept and live with their condition.

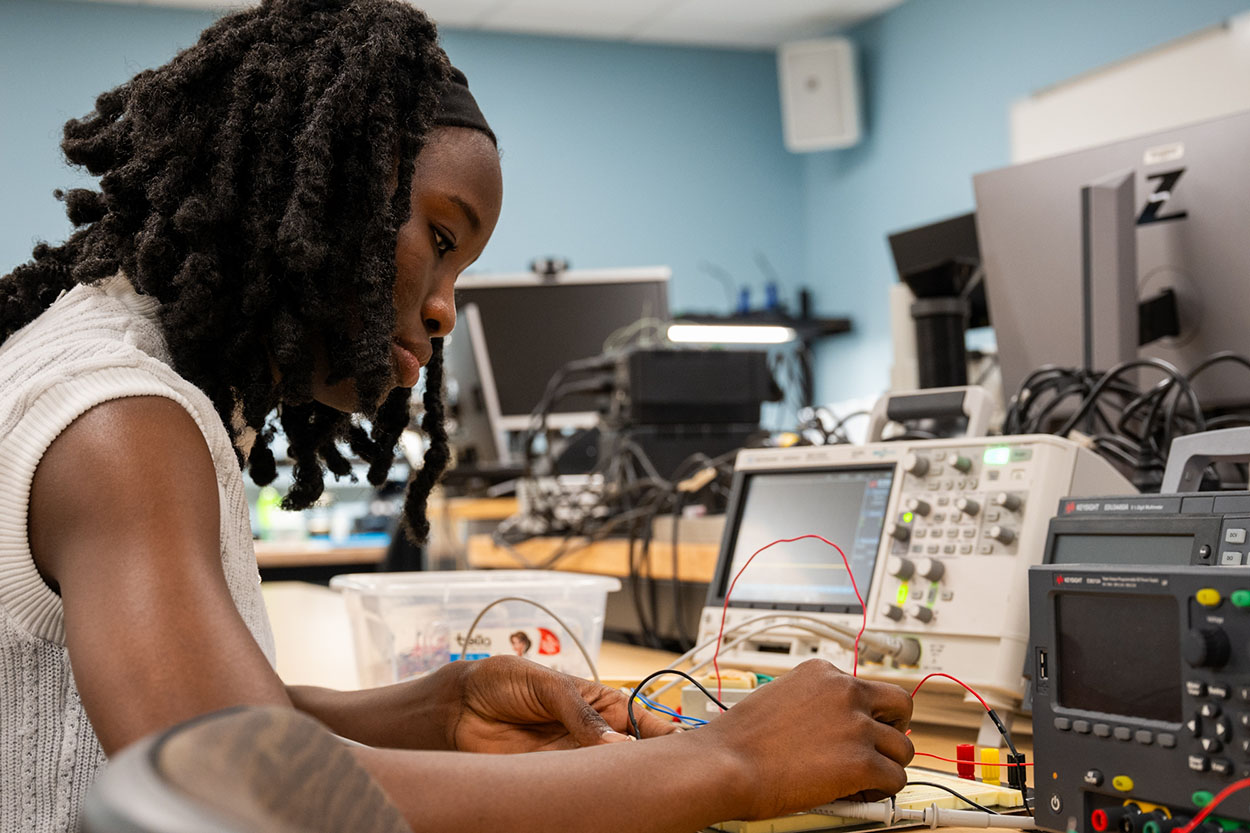

Motivated by her brother’s crisis and under the mentorship of Electrical Engineering Instructor Dr. Jacob Eapen, Segrado created an honors project titled “Seizure Detection and Mitigation.” During her research, she learned that there are products that detect and mitigate seizures, which can prevent what could be a fatal injury and save a life.

She was excited about some existing products to treat epilepsy, like the Garmin Seizure Detector. It monitors the movement of the wearer’s arm and raises an alarm if shaking, similar to a tonic-clonic seizure, is detected for more than 10 seconds.

Segrado’s project was to create a similar product in a developing country, where only 26% of the population has access to electricity, 87% in urban areas and only 7% in rural areas.

She said that if people in villages need help, they should be able to let their loved ones know that they are having a seizure. Realizing that her epileptic patients in her country have no access to help, she knows there is an urgent need.

Helpful products are available in the United States, but access to these types of products is not a reality for a struggling person in a developing country who doesn’t even have enough to eat.

In her project, using the concept of seizure detection and mitigation, she used the least expensive Garmin watch and, through the implementation, tried to understand the watch’s code and see how to manage the frequencies of the movements made by the patient during the seizure. She also collected data so it could connect to a parent, guardian or loved one’s phone. In her project, she is trying to partner with a tech company to make it affordable and accessible to those who need it most.

Segrado dreams of returning and visiting her country. Her course management and ongoing research make it challenging. Then there are the ever-changing international traveling rules that can create anxiety with anybody with a visa, creating a barrier to visiting family. However, she is confident she has chosen the right path not only for education but also for providing affordable treatment for her brother and her neighbors.